Introduction

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) evolved in the early 1990s from a niche technique for thin-film analysis into a widely adopted biosensing platform. Its ability to monitor biomolecular interactions in real time—without labeling—and to extract kinetic rate constants fundamentally transformed biophysics, structural biology, and pharmaceutical research.

The introduction of carboxymethyl dextran (CMD)-coated sensor chips played a major role in this development [1][2]. This three-dimensional hydrogel allows efficient covalent ligand immobilization within the SPR evanescent field, while preserving ligand activity. Additionally, it minimizes nonspecific adsorption to the underlying gold layer, significantly improving sensitivity and data quality. The design was commercialized as the Biacore™ CM5 sensor chip, which remains the standard for kinetic and affinity analyses.

Approximately 10 years after the introduction of CM5 chip chemistry, XanTec advanced SPR sensor surface design by replacing the traditional hydrophobic adhesion layer with a fully hydrophilic alternative. The resulting three-dimensional nanoarchitecture delivered unprecedented bioinertness and sensitivity, and now forms the basis of XanTec’s broad sensor chip portfolio. Subsequent developments—including alternative hydrogels and improved immobilization chemistries—have further strengthened XanTec’s position as a technology leader in SPR surface chemistry. These innovations are complemented by the availability of direct equivalents to Cytiva’s established sensor chip formats.

Among these, XanTec’s CMD200M—the functional counterpart to the CM5—has become one of the company’s most widely adopted sensor chips. To provide users with a rigorous performance assessment, we conducted a systematic comparison of CMD200M and CM5 formats, evaluating:

- Root mean square (RMS) noise and bulk refractive index sensitivity

- Preconcentration behavior and immobilization capacity

- Chemical stability (CMD200M only)

- Biomolecular interaction performance using Strep-Tactin XT (SXT) and carbonic anhydrase II (CAII) benchmark systems

- Nonspecific binding characteristics

This white paper summarizes the results and provides evidence-based guidance for users seeking full interoperability and seamless protocol transfer between CMD200M and CM5 sensor surfaces.

Results

To provide clear, data-driven guidance for users, CMD200M was directly evaluated against the CM5 sensor chip across all relevant performance dimensions. The results reveal how both surfaces behave under identical experimental conditions, and where CMD200M offers measurable advantages.

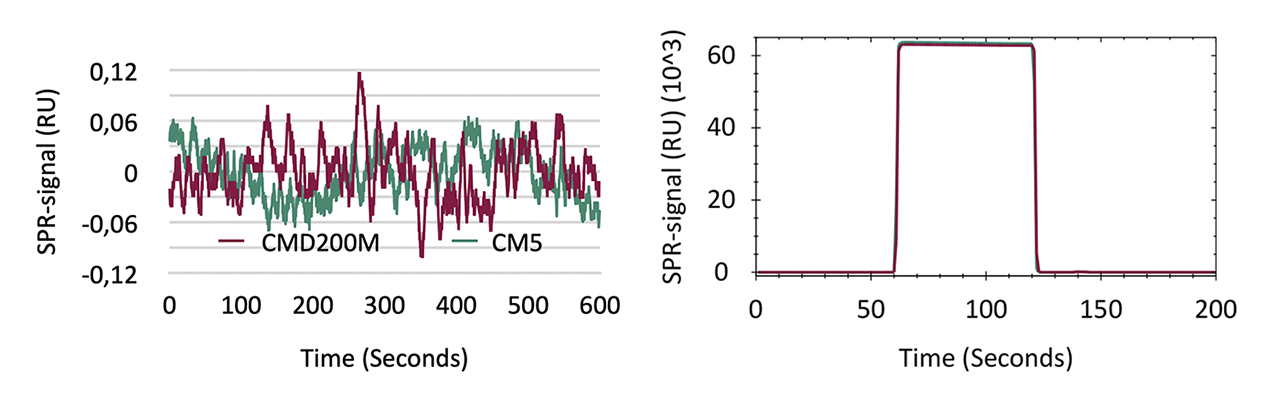

Optical characteristics

Optical assessment of both sensor chips revealed neglectable differences. Both sensor chips displayed RMS noise ≤ 0.033 RU over a period of 600 s. The bulk refractive index sensitivity—determined by the SPR signal shift after injection of 50% glycerol in water—varied by < 1 %, indicating a similar occupation of the evanescent field by the CMD hydrogel matrix.

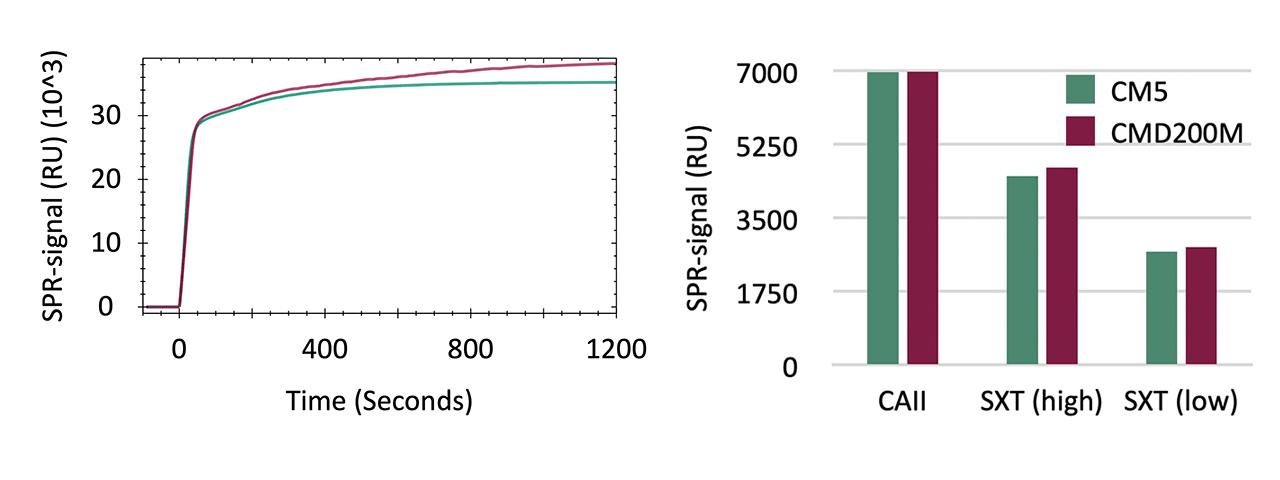

Immobilization capacity and coupling yield

Likewise, preconcentration capacity and covalent coupling efficiency—an important metric for sensor chip sensitivity—were highly comparable, with maximum deviation < 7 % (Fig. 2). Removal of preconcentrated protein using phosphate elution buffer was virtually quantitative. These results confirm that proteins differing in size and charge exhibit similar coupling efficiencies on both matrices, indicating no significant difference in immobilization performance.

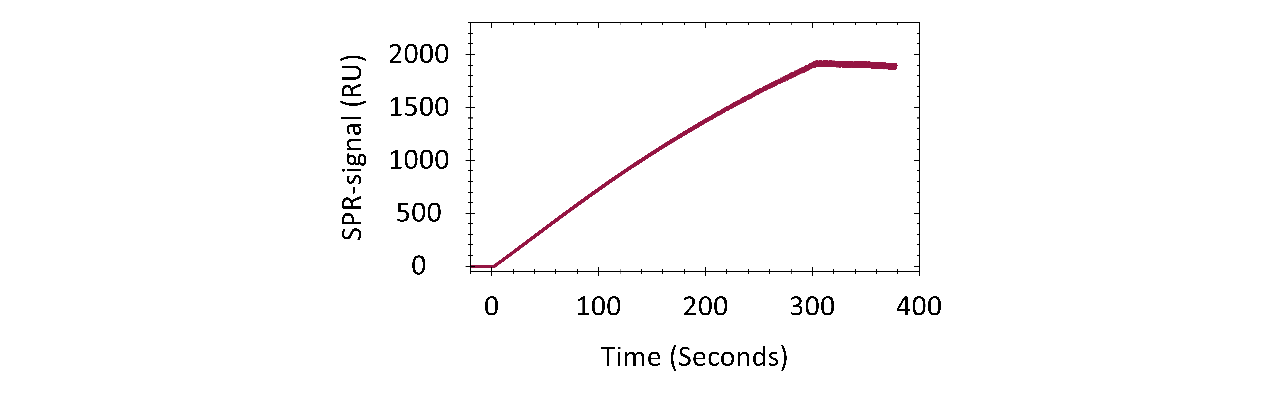

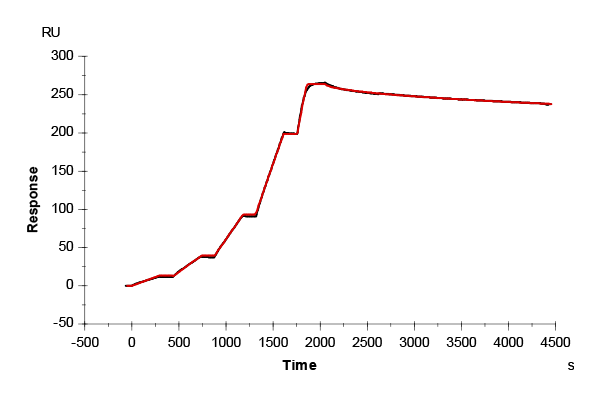

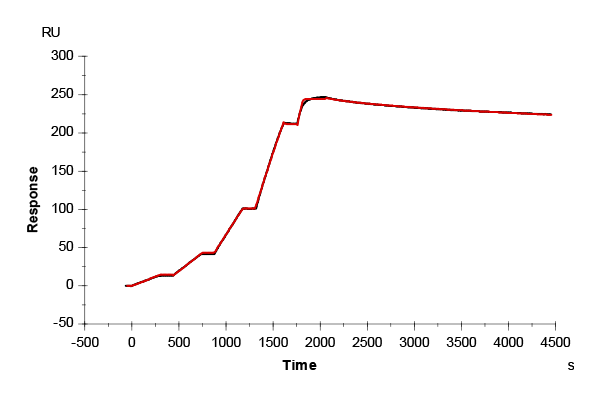

Chemical stability

Moreover, CMD200M exhibited excellent chemical robustness and cycle stability. This was demonstrated by 39 consecutive capture-regeneration cycles of pooled rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) on a Protein A/G–modified CMD200M sensor chip (Fig. 3). Regeneration was performed under alternating acidic (10 mM glycine, pH 1.5) and alkaline (20 mM NaOH) conditions. The average capture response across all cycles was 1905 RU after 390 s (SD = 8.4 RU ± 0.4 %), with no detectable decline in signal over time, demonstrating stable and reproducible performance across repeated use. Based on this stability profile, the CMD200M sensor chip is expected to tolerate hundreds of such regeneration cycles without compromising data quality.

Kinetic assessment

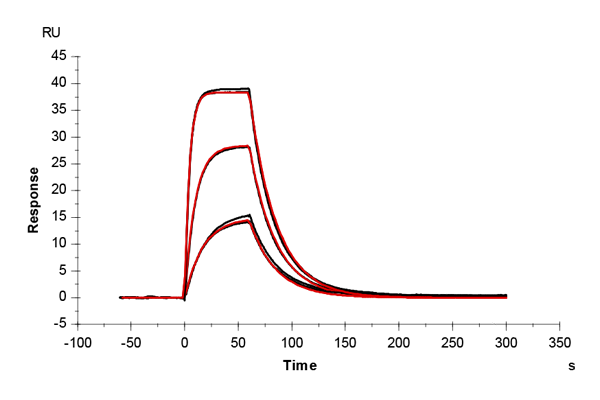

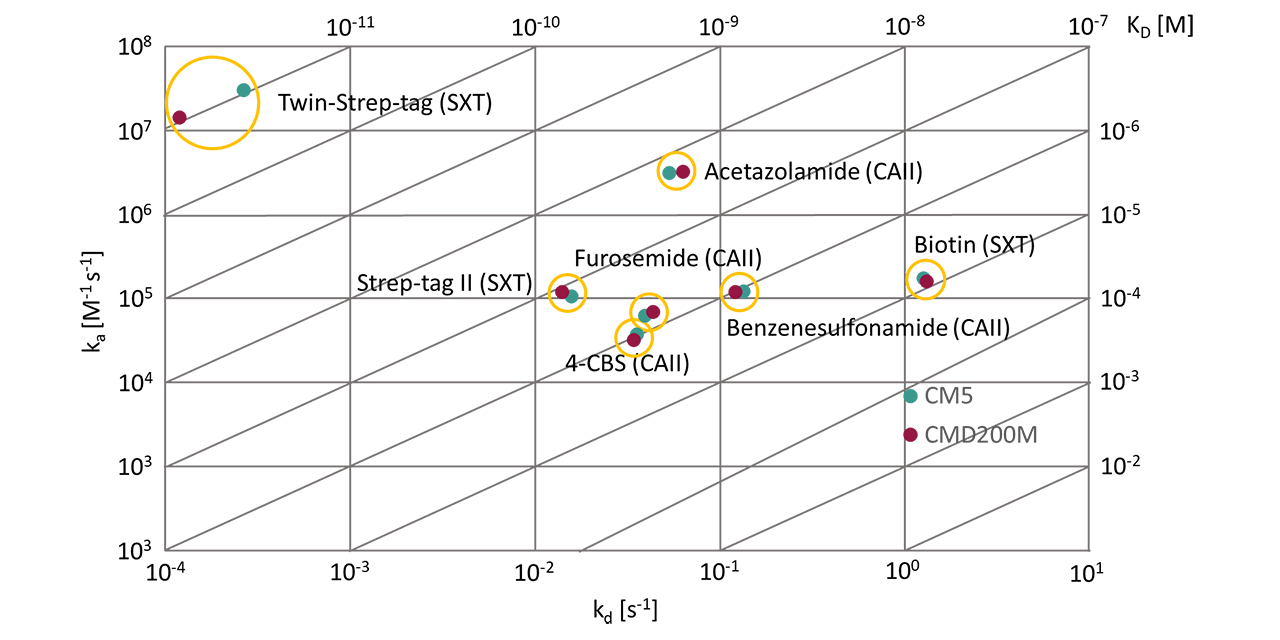

Building on these findings, both sensor chips were further evaluated to determine whether systematic deviations in equilibrium or rate constants occur during biomolecular interaction analysis. Two model systems were selected for this purpose. The first used the zinc-containing metalloenzyme CAII that catalyzes the reversible hydration of carbon dioxide to bicarbonate and protons. Due to its well-characterized structure, high stability, and reproducible immobilization, CAII serves as a benchmark protein for assessing small-molecule binding in SPR [3][4]. Its sulfonamide-based inhibitors cover affinity ranges from micromolar to nanomolar, making it ideal for sensor chip comparison. Meanwhile, the Strep-Tactin XT platform extends the benchmark to larger peptide analytes [5]. Here, affinity increased with analyte size, from biotin (240 Da) to Strep-tag II (1.1 kDa) and Twin-Strep-tag (3 kDa), spanning micromolar to picomolar equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) values.

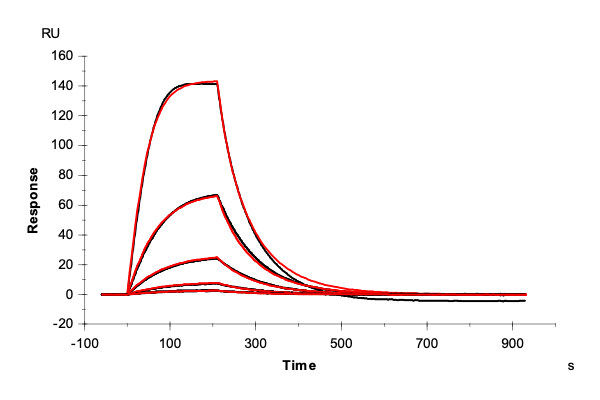

Kinetic analysis (Tabs. 1 and 2, and Fig. 4) demonstrated close agreement between CMD200M and CM5 across both model systems, covering analytes from ~160 Da to 3 kDa and affinities from µM to pM. Overall, association (kₒn) and dissociation (koff) rates differed by 10 ± 6 % (6 of 7 cases), and KD values by 11 ± 7 %, well within typical experimental variability. Global 1:1 Langmuir fits described all data accurately, indicating no mass-transport or surface heterogeneity effects.

The only notable deviation occurred in the Twin-Strep-tag/Strep-Tactin XT interaction, where CMD200M showed ~50 % faster association and dissociation rates, indicating a reduced diffusion limitation. Notably, CMD200M also produced lower χ² values in 5 of 7 measurements—although the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.3)—indicating a trend toward improved fit quality. This effect may be linked to decreased nonspecific binding, as discussed in the following section.

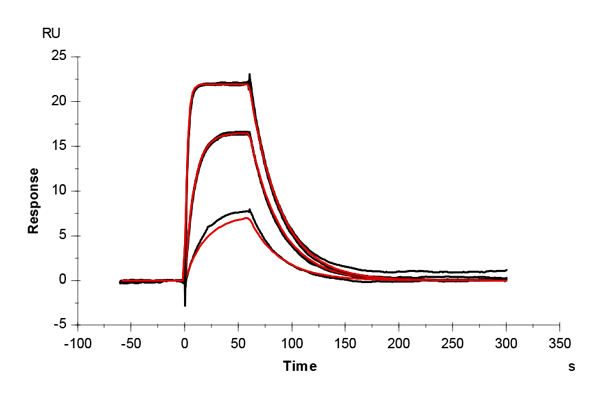

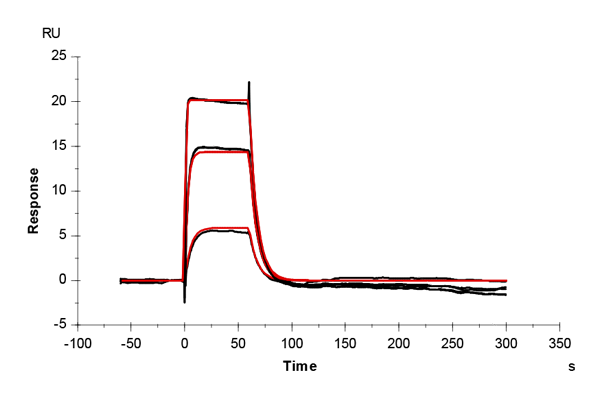

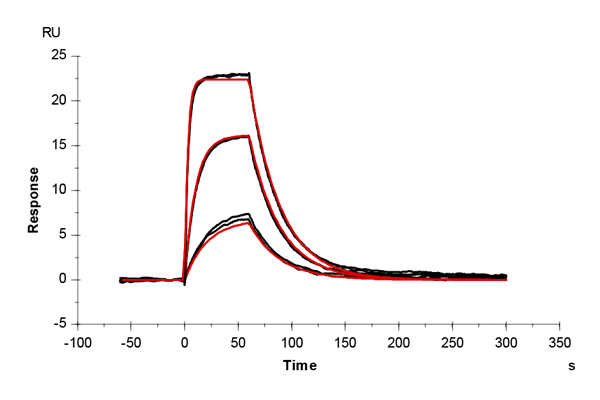

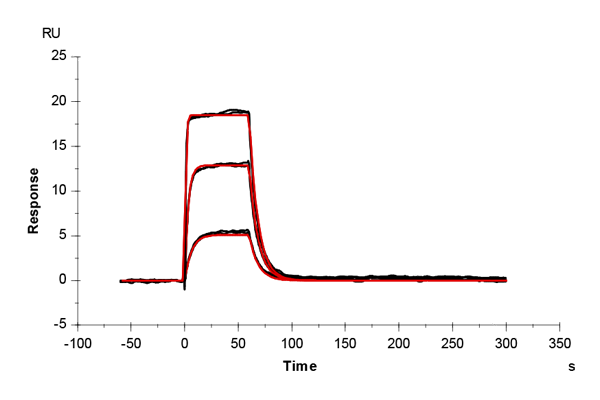

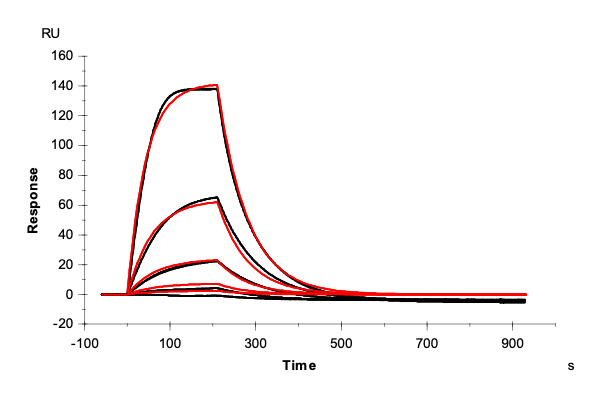

Table 1: Overlay plots of the interaction analysis of immobilized CAII versus furosemide, 4-CBS, benzenesulfonamide, and acetazolamide on CM5 and CMD200M sensor chips. Experimental data are shown in duplicate (black). Corresponding binding models are colored red. Kinetic rate and equilibrium constants extracted from the models for both CM5 and CMD200M sensor chips are presented below.

| Furosemide | 4-CBS | Benzenesulfon-amide | Acetazolamide | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CM5 |  |

|

|

|

|

| CMD200M |  |

|

|

|

|

| ka [M-1 s-1] | CM5 | 6.27E+04 | 3.78E+04 | 1.22E+05 | 3.10E+06 |

| CMD 200M | 6.94E+04 | 3.21E+04 | 1.20E+05 | 3.22E+06 | |

| kd [s-1] | CM5 | 0.040 | 0.036 | 0.136 | 0.054 |

| CMD 200M | 0.044 | 0.035 | 0.123 | 0.064 | |

| KD [M] | CM5 | 6.34E-07 | 9.55E-07 | 11.2E-07 | 1.74E-08 |

| CMD 200M | 6.35E-07 | 10.76E-07 | 10.2E-07 | 1.99E-08 | |

| Chi2 | CM5 | 0.165 | 0.188 | 0.387 | 0.198 |

| CMD 200M | 0.200 | 0.145 | 0.247 | 0.062 |

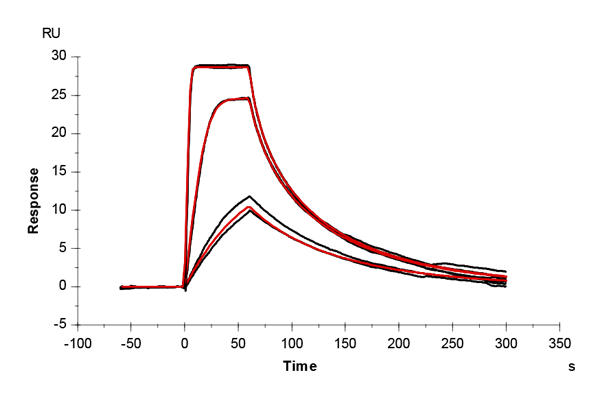

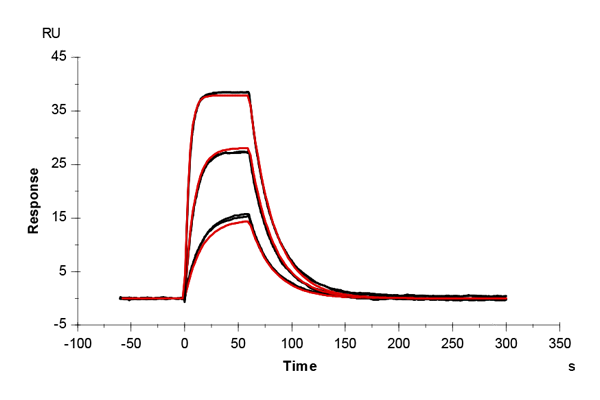

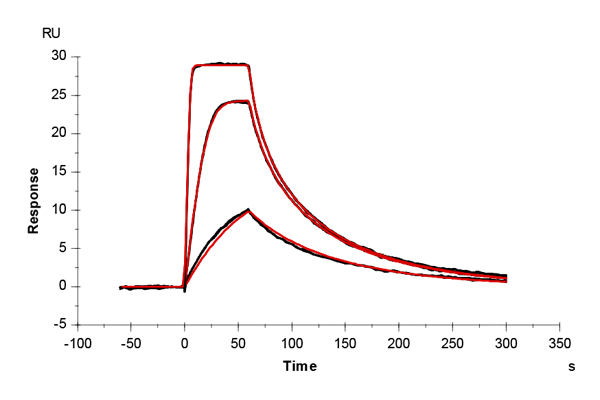

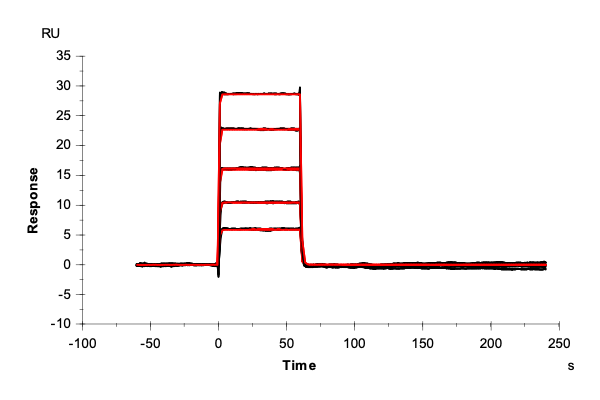

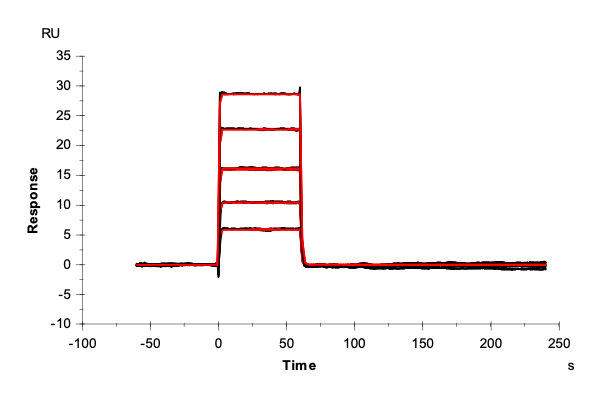

Table 2: Overlay plots of the interaction analysis of immobilized Strep-Tactin XT versus biotin, Strep-tag-II, and Twin-Strep-tag on CM5 and CMD200M sensor chips. Experimental data are shown in duplicate (black). Corresponding 1:1 binding models are colored red. Kinetic rate and equilibrium constants extracted from the model for both CM5 and CMD200M sensor chips are presented below.

| Biotin | Strep tag II® | Twin-Strep-tag® | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CM5 |  |

|

|

|

| CMD200M |  |

|

|

|

| ka [M-1 s-1] | CM5 | 1.73E+05 | 1.06E+05 | 2.99E+07 |

| CMD 200M | 1.59E+05 | 1.19E+05 | 1.40E+07 | |

| kd [s-1] | CM5 | 1.29 | 1.59E-02 | 2.65E-04 |

| CMD 200M | 1.35 | 1.42E-02 | 1.19E-04 | |

| KD [M] | CM5 | 7.46E-06 | 1.50E-07 | 8.85E-12 |

| CMD 200M | 8.48E-06 | 1.19E-07 | 8.52E-12 | |

| Chi2 | CM5 | 0.0763 | 9.91 | 1.06 |

| CMD 200M | 0.172 | 2.76 | 0.796 |

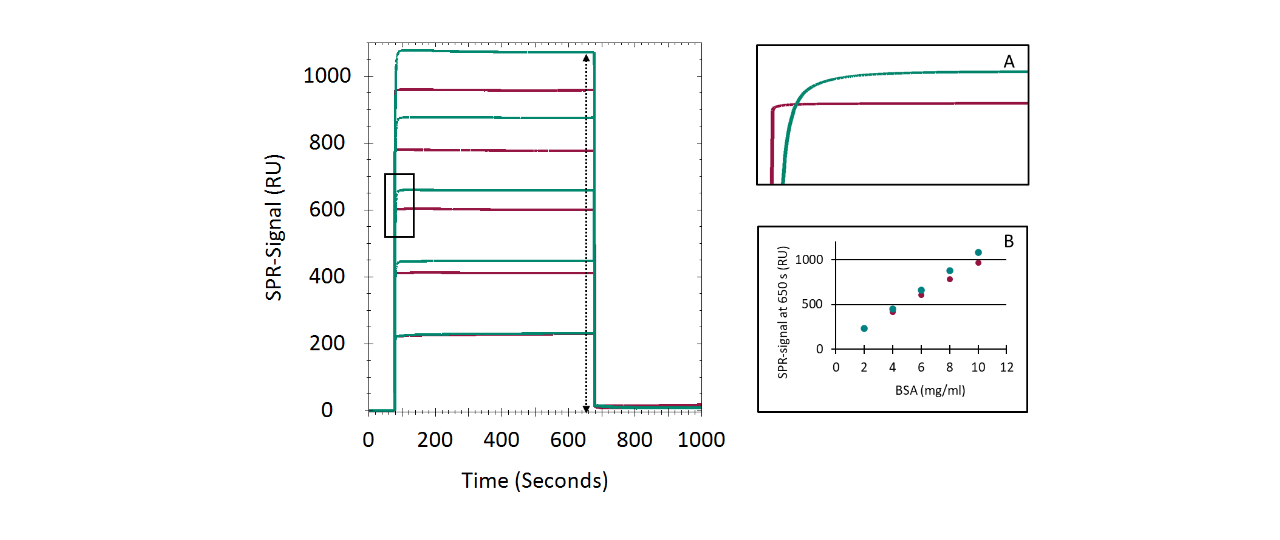

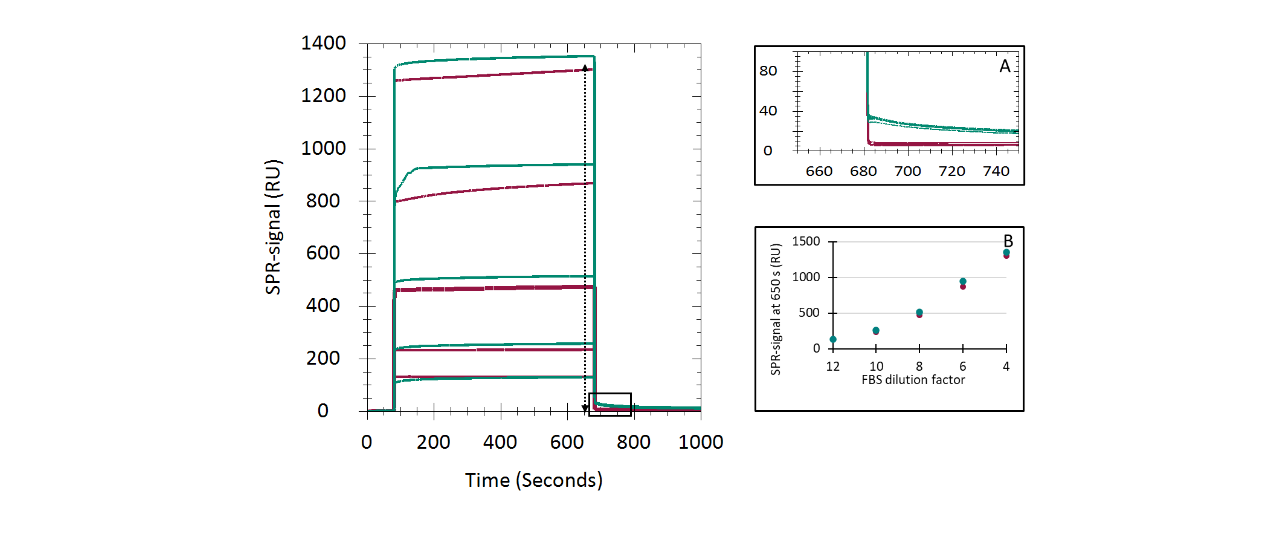

Nonspecific binding

CMD200M and CM5 showed remarkable similarity in both immobilization performance and biomolecular interaction analysis outcomes. However, the slightly better fit quality observed for CMD200M and the lower apparent diffusion limitation in the Strep-Tactin XT/Twin-Strep-tag system prompted a more detailed investigation of nonspecific binding (NSB). In BSA adsorption experiments, CMD200M and CM5 produced similar concentration-dependent responses; CMD200M reached steady state faster, while CM5 showed ~10 % higher plateau levels. Dissociation was rapid and nearly complete on both surfaces, indicating weak, reversible interactions. In fetal bovine serum (FBS) adsorption experiments, NSB on both chips showed strong concentration dependence, but CM5 exhibited slower, concentration-independent signal decay, suggesting more persistent NSB of certain serum components. Overall, both chips displayed low nonspecific adsorption, yet CMD200M showed faster equilibration and cleaner dissociation, indicating a slightly reduced tendency for NSB compared to CM5, likely due to the improved adhesion promoter chemistry of the CMD200M chip surface.

Conclusion

Across both biological systems—spanning small-molecule-protein and peptide-protein interactions—the results demonstrate that assays established on CM5 can be directly transferred to CMD200M (and vice versa) without systematic bias. Pre-concentration and immobilization capacities as well as experimental outcomes are highly comparable. The chemical stability of CMD200M was excellent. This equivalence allows users to interchange both sensor types on Biacore™ instruments and supports cross-platform comparability. While Biacore™ CM sensor chips are limited to Biacore™ hardware, CMD200M provides a vendor-independent, cost-effective alternative, enabling reliable comparison of results and seamless protocol transfer between different SPR systems. Although overall performance is highly similar, CMD200M exhibited lower nonspecific binding, as observed with BSA and FBS, and slightly lower χ² values in kinetic fits. These differences indicate a trend toward improved data quality.

Taken together, these results clearly show that CMD200M performs on par with CM5 while providing superior versatility, lower background, and excellent cost efficiency. Users can therefore adopt CMD200M with complete confidence—without compromise in data integrity or performance. In addition, XanTec’s HC30M sensor chip provides an even more versatile option: its thinner hydrophilic matrix reduces diffusional constraints, enabling reliable kinetic analysis across a broader analyte size range—from small molecules to large proteins and antibodies. By comparison, the thicker CM5 and CMD200M coatings can introduce diffusion-limiting effects for high-molecular-weight analytes —particularly for interactions with fast association and dissociation rates— potentially distorting the extracted kinetic constants under certain conditions [6].

Materials and Methods

Materials

BSA and CAII (from bovine erythrocytes, ≥ 90% purity by SDS-PAGE), as well as 4-carboxybenzenesulfonamide (4-CBS), benzenesulfonamide, furosemide, and acetazolamide were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Strep-Tactin XT (SXT), Strep-tag II, and Twin-Strep-tag peptides were purchased from IBA Lifesciences (Göttingen, Germany). Biotin was supplied by Carl Roth (Karlsruhe, Germany). FBS was from Biowest (Nuaillé, France). Protein A/G (PAG) was supplied by ProSpec (Rehovot, Israel).

Pre-mixed buffers and coupling reagents—including Activation Buffer, 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC-HCl), ethanolamine-HCl, acetate coupling buffer, glycine, NaOH, and concentrated stock solutions (10× PBS, 10× PBST, 10× HBSTE)—were supplied by XanTec bioanalytics (Düsseldorf, Germany). All chemicals were of analytical grade (p.a.). Buffers and stock solutions were prepared with ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ·cm) and sterile-filtered (0.22 µm) prior to use.

Protein samples were stored at –80 °C (SXT, 2.5 mg/mL in PBS; CAII, 5 mg/mL in PBS). Sensor chips used in this study were CM5 (Cytiva, Uppsala, Sweden) and CMD200M (XanTec bioanalytics), stored according to manufacturer recommendations (Cytiva 4–8 °C; XanTec –20 °C).

Instrument setup

All SPR measurements were performed on a Biacore™ T200 (Cytiva) at 25 °C with a 10 Hz sampling rate. Before each experimental series, the instrument was cleaned using the Desorb protocol and primed for 7 min with running buffer. New sensor chips were preconditioned by injecting phosphate elution buffer (0.1 M HxNayPO₄, 1 M NaCl, pH 7.0; 60 s, 50 µL/min). Baseline stability was confirmed by five buffer blanks, and all kinetic data were processed using double referencing.

RMS evaluation

The sensor surface was conditioned as described above and equilibrated in running buffer (PBS + 0.03% sodium azide) until a stable baseline was achieved. The SPR signal was recorded for 600 s at 50 µL/min.

Bulk refractive index sensitivity

After sensor conditioning and equilibration in running buffer (PBS + 0.03% sodium azide), a 50 % (v/v) glycerol solution (diluted in water) was injected three times for 60 s each (50 µL/min).

BSA preconcentration

Following surface conditioning, the chip was equilibrated in ultrapure water. BSA (100 µg/mL in 5 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.0) was injected (10 µL/min; 1200 s association; 60 s dissociation), followed by rinsing with phosphate elution buffer to remove electrostatically bound protein.

CAII immobilization and inhibitor binding

CM5 and CMD200M chips were activated by mixing 0.4 M EDC dissolved in water with Activation Buffer (0.1 M N-hydroxysuccinimide in 0.05 M MES, pH 5.0) in a 1:1 ratio and injecting the freshly prepared solution for 7 min at 10 µL/min. CAII (250 µg/mL in 5 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.7) was then injected over flow channel 2–4 for 7 min; flow channel 1 served as the reference surface. Remaining active esters were quenched with 1 M ethanolamine-HCl (pH 8.5) for 7 min, typically yielding 6,900–7,000 RU of immobilized CAII.

Interaction analyses with CAII inhibitors were performed in PBS + 3% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Compounds were diluted from 1 mg/mL DMSO stocks to final concentrations of 0.016–10 µM (4-CBS: 0.4, 2.0, 10 µM; acetazolamide: 0.016, 0.08, 0.4 µM; benzenesulfonamide: 0.4, 2.0, 10 µM; furosemide: 0.3, 1.0, 3.0 µM). Duplicate injections (100 µL/min; 60 s association; 240 s dissociation) were globally fitted to a 1:1 Langmuir model (Biacore™ T200 Evaluation Software v3.2.1).

Strep-Tactin XT immobilization and analyte binding

SXT immobilization was performed using the same activation chemistry as for CAII. SXT (25 µg/mL in 5 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.5) was injected for 10 min over flow channel 2, then for 5 min over flow channel 4, resulting in immobilization levels of 4,500–4,700 RU (CH2, high-density surface) and 2,800 RU (CH4, low-density surface).

Biotin binding was measured in PBST + 3% DMSO using 0.625–10 µM biotin (2-fold serial dilution). Duplicate injections were performed (100 µL/min; 60 s association; 180 s dissociation) and evaluated using a 1:1 Langmuir model.

Interactions with Strep-tag II and Twin-Strep-tag peptides were performed in HBSTE (10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 0.005% Tween-20, 50 µM EDTA, pH 7.4).

Strep-tag II: 1–90 nM analyte (70 µL/min; 210 s association; 720 s dissociation) with intermediate blanks. Data were analyzed in TraceDrawer v. 1.10 (Ridgeview Instruments) using a 1:1 model with mass transport limitation (MTL) correction.

Twin-Strep-tag: Twin-Strep-tag interactions were measured using a kinetic titration protocol. Sequential injections of 0.625–10 nM analyte (2-fold dilution series) were applied with 300 s association and 180 s dissociation phases (70 µL/min), followed by a final extended dissociation of 2,400 s after the highest concentration. Sensorgrams were globally fitted using Biacore™ Evaluation Software v3.2.1.

Chemical stability (PAG immobilization and IgG binding)

PAG was immobilized using the same activation chemistry as described for CAII. PAG (25 µg/mL in 5 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.0) was injected over flow channel 4 for 12 min, yielding ~2,000 RU of immobilized PAG; flow channel 1 served as the reference. Prior to the IgG capture experiment, the surface was conditioned with short pulses of 10 mM glycine-HCl (pH 1.5) and 20 mM NaOH (30 s each, 50 µL/min).

IgG-binding experiments were performed in PBS supplemented with 0.1% (w/v) BSA. IgG (2.5 µg/mL) was injected for 5 min at 10 µL/min, followed by a 30 s stabilization period. After each cycle, the surface was regenerated by sequential injections of 10 mM glycine-HCl (pH 1.5, 30 s, 50 µL/min) and 20 mM NaOH (30 s, 50 µL/min), each followed by 30 s stabilization.

Nonspecific binding assays

Sensor chips were primed with PBS. BSA (2–10 mg/mL in PBS) was injected sequentially (15 µL/min; 600 s association/dissociation), followed by regeneration with phosphate elution buffer (60 s, 50 µL/min). For FBS, dilutions of 1:12–1:4 (v/v) in PBS were injected under identical conditions.

Literature

- Löfås, S., & Johnsson, B. (1990). A novel hydrogel matrix on gold surfaces in surface plasmon resonance sensors for fast and efficient covalent immobilization of ligands. Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications, 1990, 1526–1528. https://doi.org/10.1039/C39900001526

- Johnsson, B., Löfås, S., & Lindquist, G. (1991). Immobilization of proteins to a carboxymethyldextran-modified gold surface for biospecific interaction analysis in surface plasmon resonance sensors. Analytical Biochemistry, 198, 268–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2697(91)90424-R

- Myszka, D. G. (2004). Analysis of small-molecule interactions using Biacore™ S51 technology. Analytical Biochemistry, 329, 316–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ab.2004.03.028

- Papalia, G. A., Giannetti, A. M., Arora, N., Myszka, D. G., & Hopkins, A. L. (2006). Comparative analysis of 10 small molecules binding to carbonic anhydrase II by different investigators using Biacore™ technology. Analytical Biochemistry, 359, 94–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ab.2006.08.004

- Schmidt, T. G. M., Eichinger, A., Schneider, M., et al. (2021). The role of changing loop conformations in streptavidin versions engineered for high-affinity binding of the Strep-tag II peptide. Journal of Molecular Biology, 433, 166893. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2021.166893.

- Brown, Michael E., Daniel Bedinger, Asparouh Lilov, Palaniswami Rathanaswami, Maximiliano Vásquez, Stéphanie Durand, Ian Wallace-Moyer et al. „Assessing the binding properties of the anti-PD-1 antibody landscape using label-free biosensors.“ PLoS One 15, no. 3 (2020): e0229206. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229206

Disclaimer

The results presented were obtained under proprietary procedures described above. Alternative conditions and materials were not assessed and may lead to different outcomes.

Use of XanTec sensor chips does not affect the instrument warranty or any existing service contracts.

Biacore™ is a registered trademark of Cytiva.